Lately I have gotten access to an xtool F1 Ultra. One of the advantages of this laser is its ability to ablate (I wont say cut) metal. I’ve seen videos of people making pcb solder paster stencils, or cutting really thin metal on similar fiber lasers, and I wanted to try too. All of this is applicable to making small “positive” parts with the xtool as well. Here are my notes.

Settings and Cut Ordering

When working with thin material, its important not to heat the metal up too much in one spot. This means making many light passes is better than a single, really aggressive pass. This is especially true for cutting out tiny windows, or cutting out a thin “web” between two windows. Too much heat too fast will distort the final geometry.

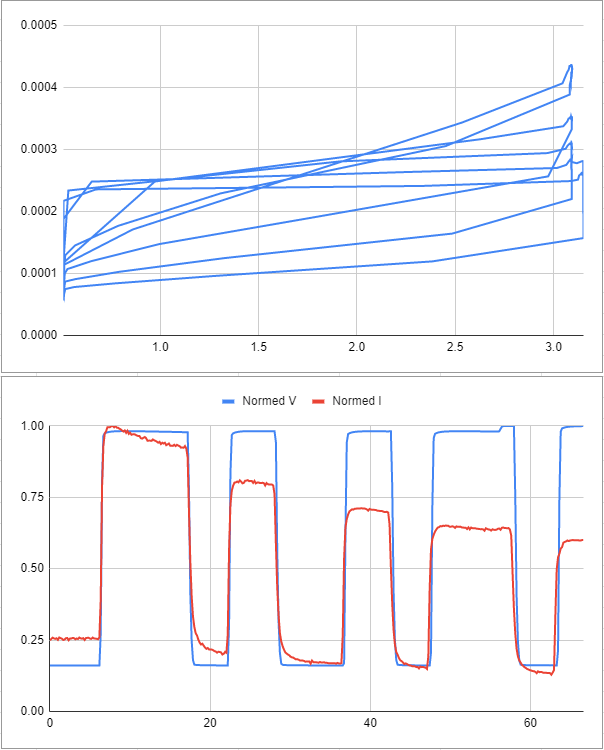

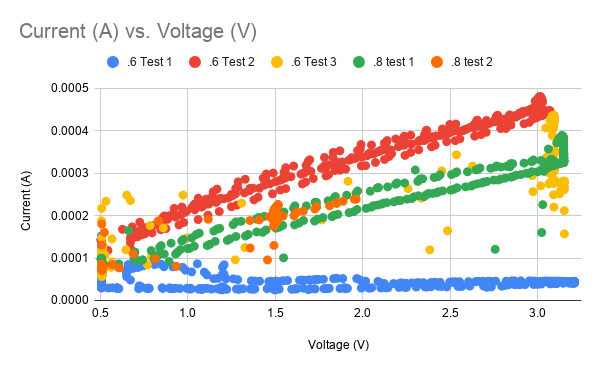

The settings I used were 100% power, 8000 mm/s speed, and a variable number of passes. For a single large cut/window (like a ~3mm square or above) you can just go ahead and set it to 500 passes and let it rip. The cut is long enough that by the time the laser comes around again, the heat has had time to conduct away.

Below about that size of window, I had better results from repeated cuts – e.g. cut 50x times, wait 10 seconds, then repeat 10x for a total of 500 cuts.

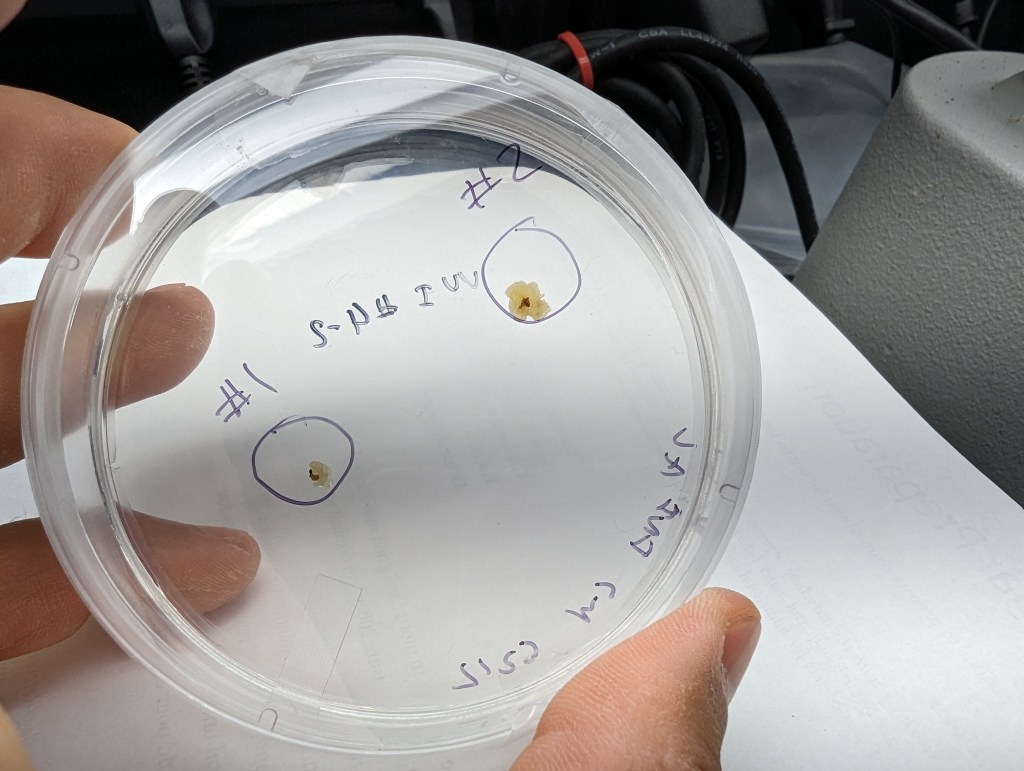

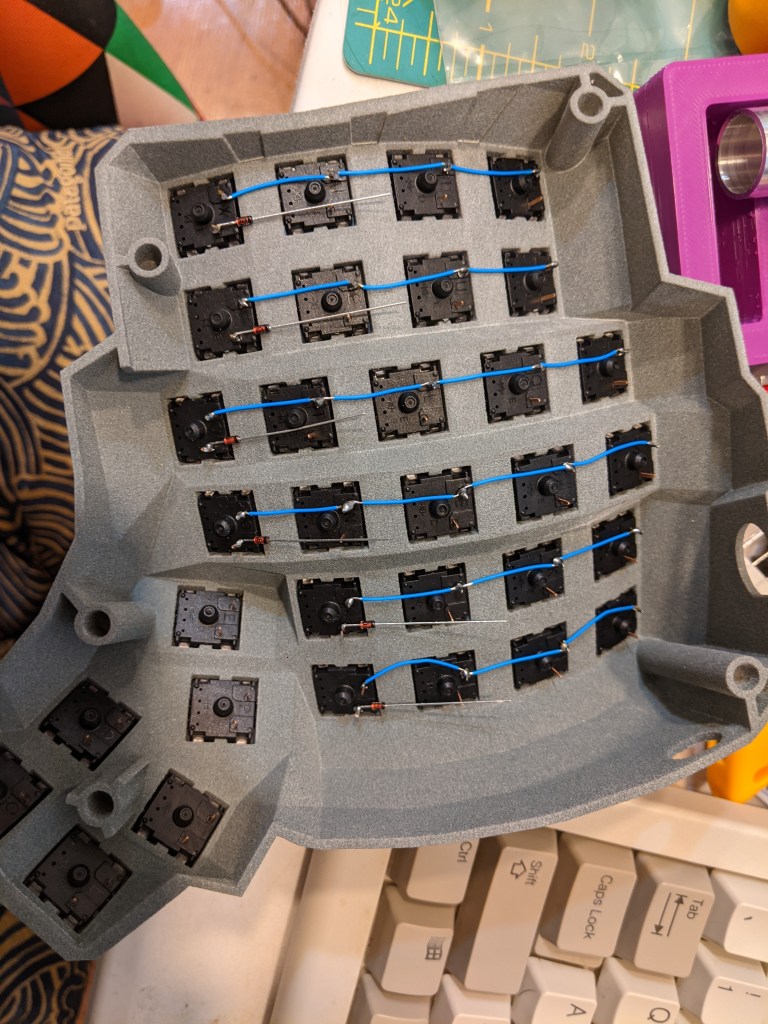

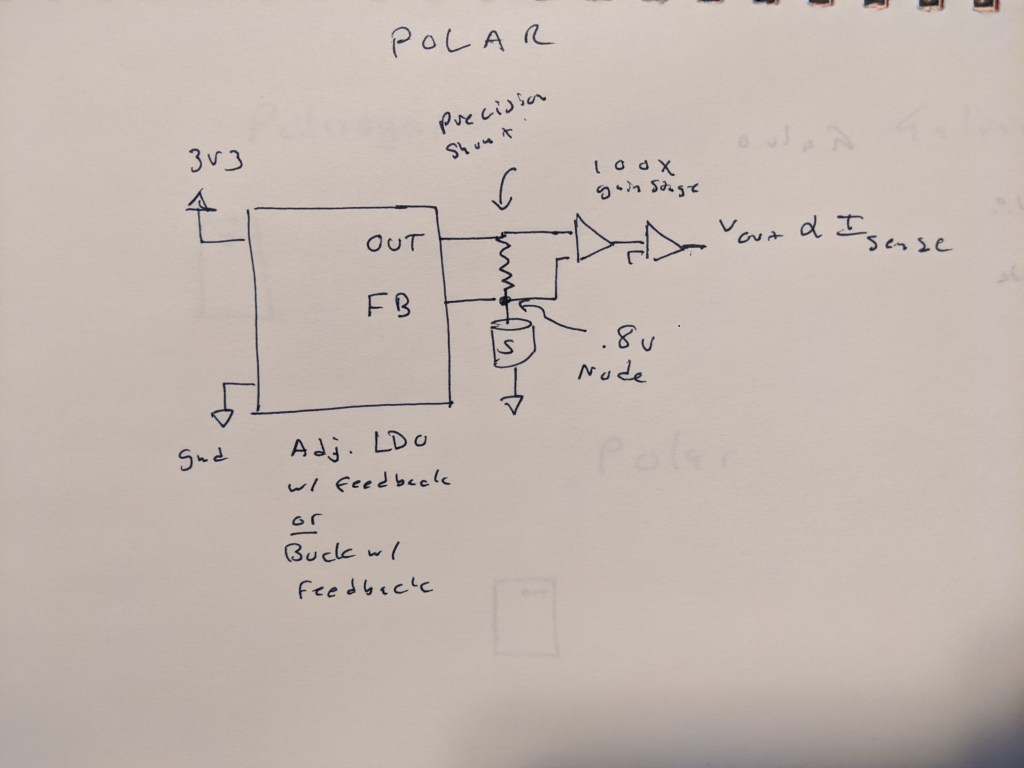

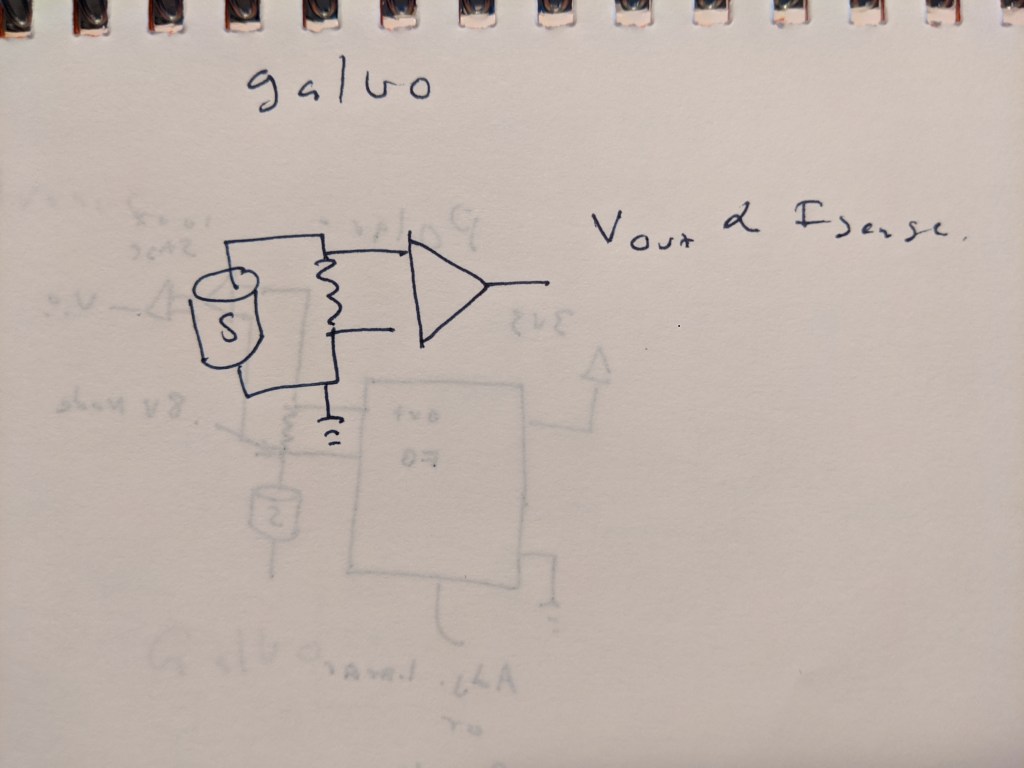

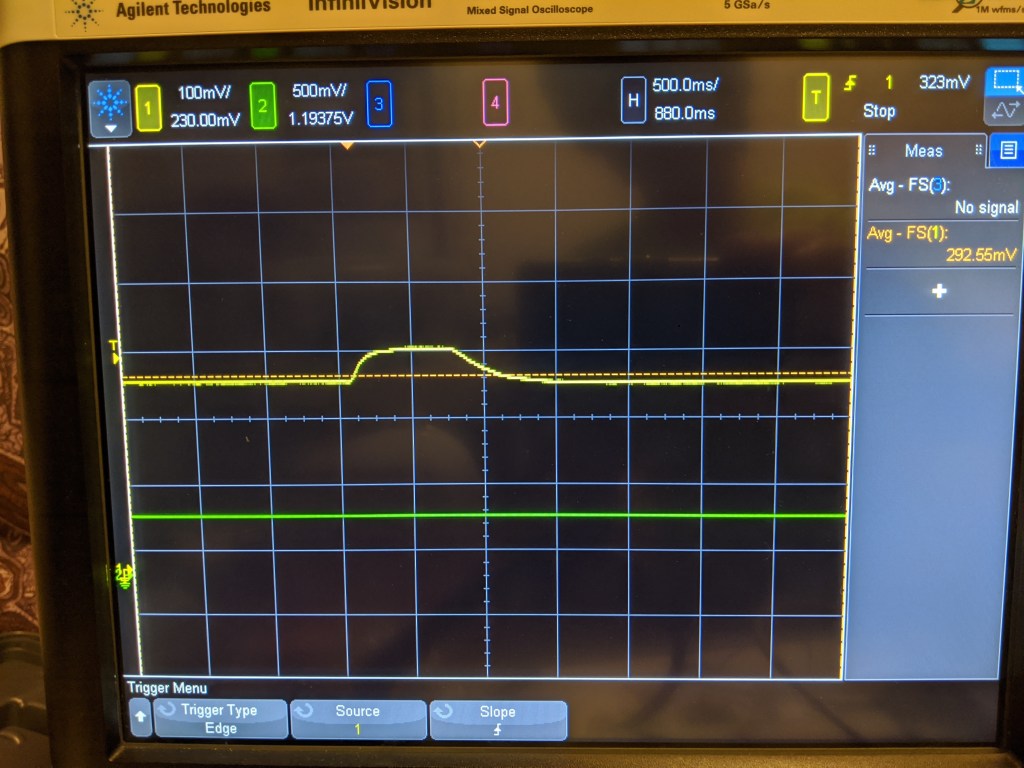

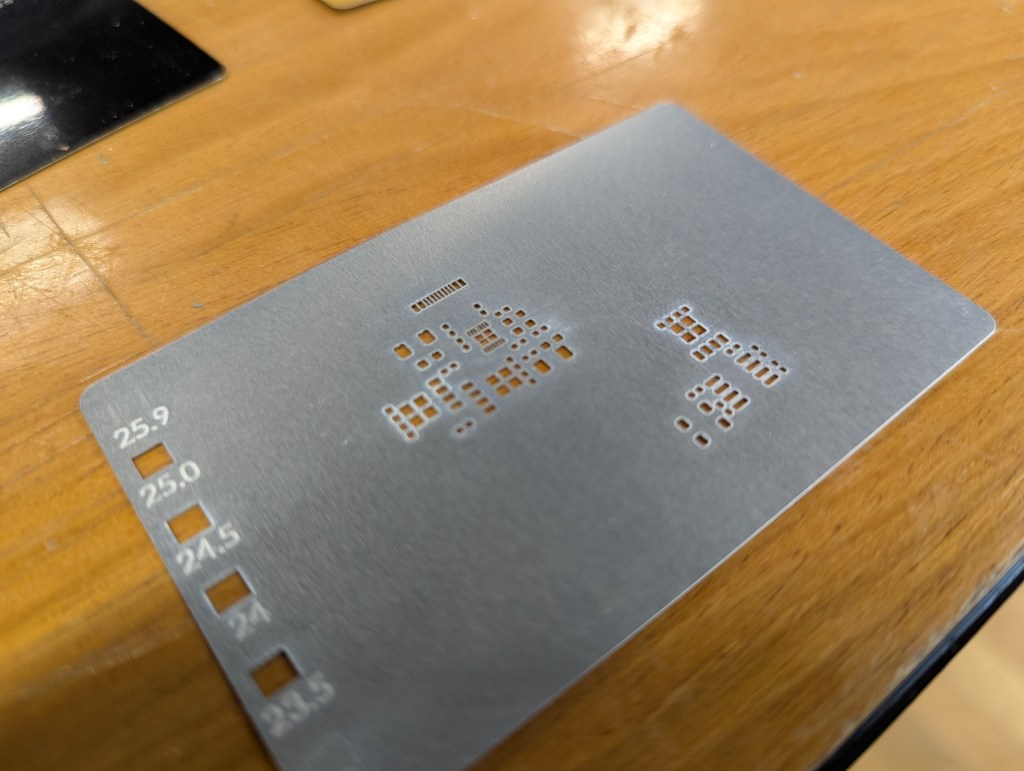

In addition to taking many passes, I needed to semi-randomize the ordering of the cuts. The Xtool sofware optimizes for time, by cutting from the top left to bottom right. This means that cut profiles that are next to each other together are done at the same time. This leads to overheating local overheating, and warping. The left stencil was randomized, the right one was not.

Sadly, there is not feature to do this in the xtool studio. The best you can do is select->ungroup your stencil, then go through and assign each cut in your stencil to a different layer. Then, using the “…” menu near the process button, choose processing path-> user defining and choose “by layer”. There are about 10 default layers, so the laser will go “somwhere else” for about 9 cuts before returning to where it was cutting before. This greatly reduces local heating.

Workholding to Prevent Warping

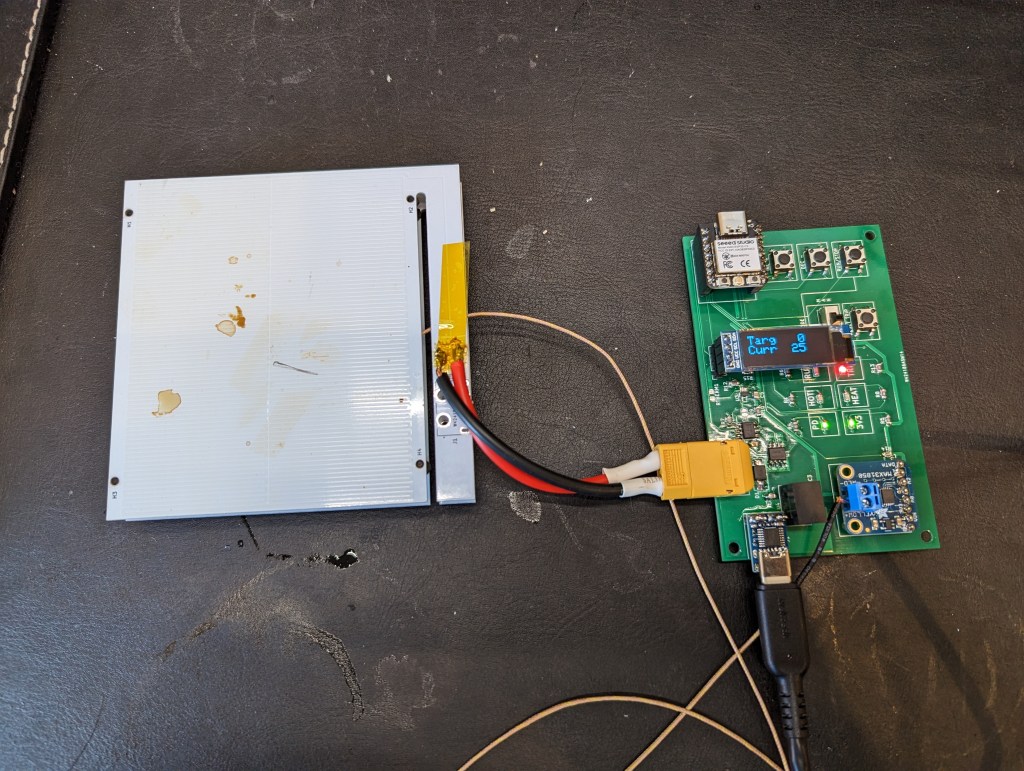

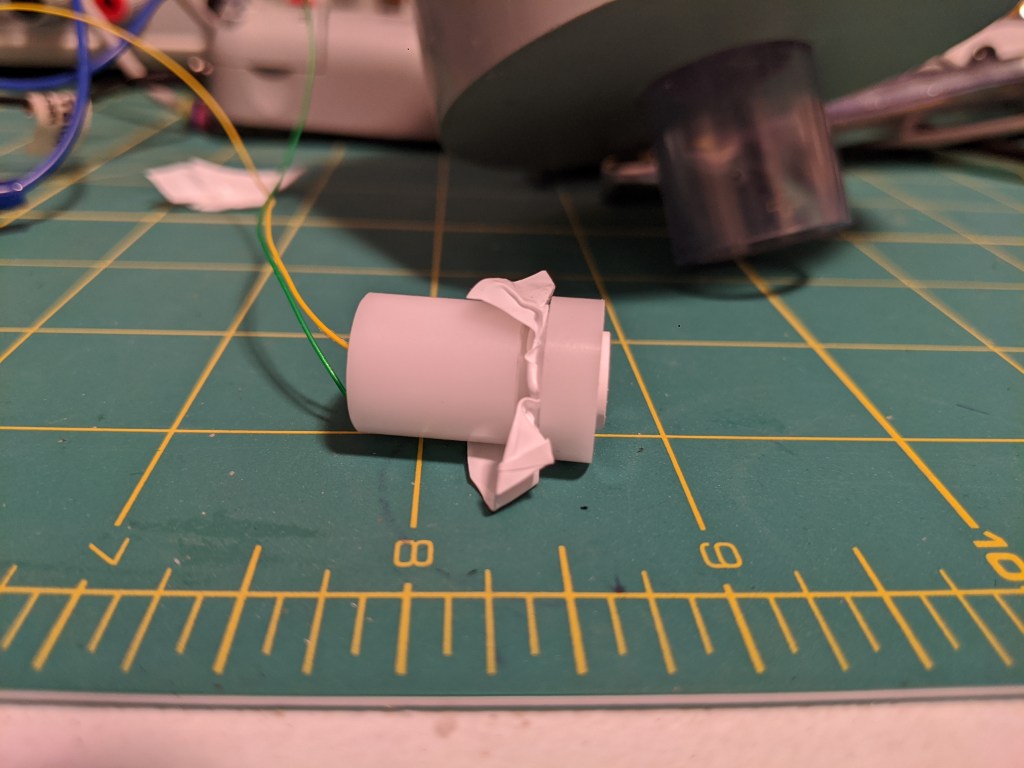

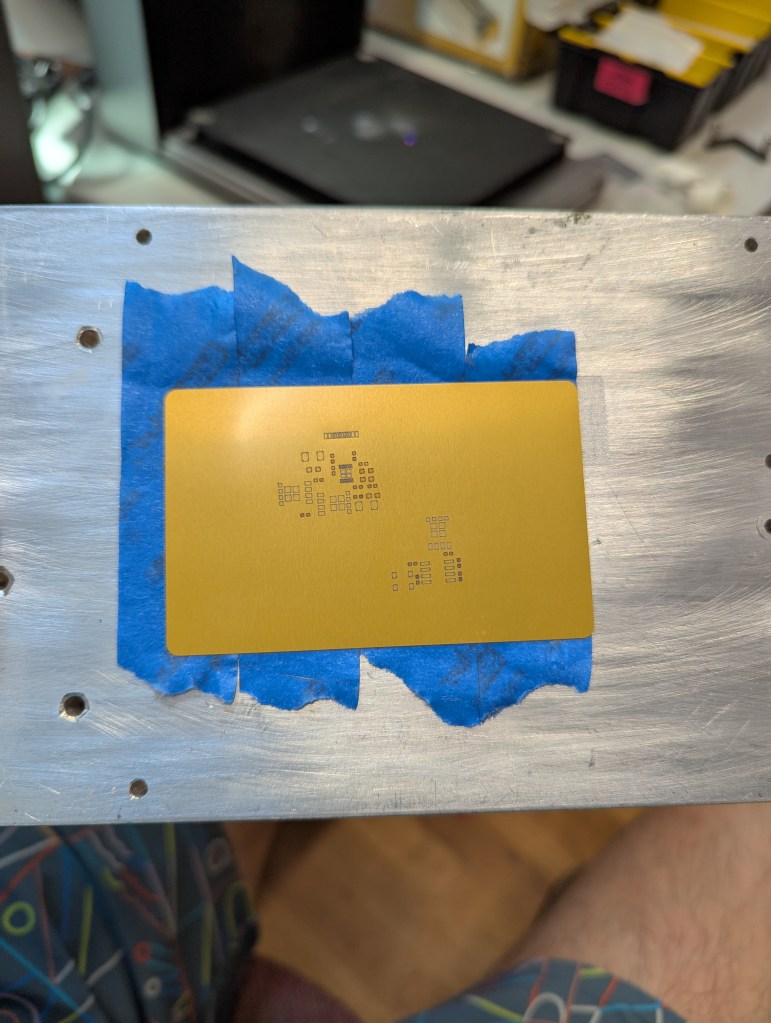

Warping happens when some part of the aluminum gets so hot that it expands, and causes plastic (permeant) deformation in the rest of the sheet of aluminum. To avoid this, I constrained the sheet with tape. This prevents deformation in exchange for stress in the aluminum. By minimizing heating, we minimize this stress.

This fixturing also holds the aluminum material so it doesn’t move due to the exhaust fan.

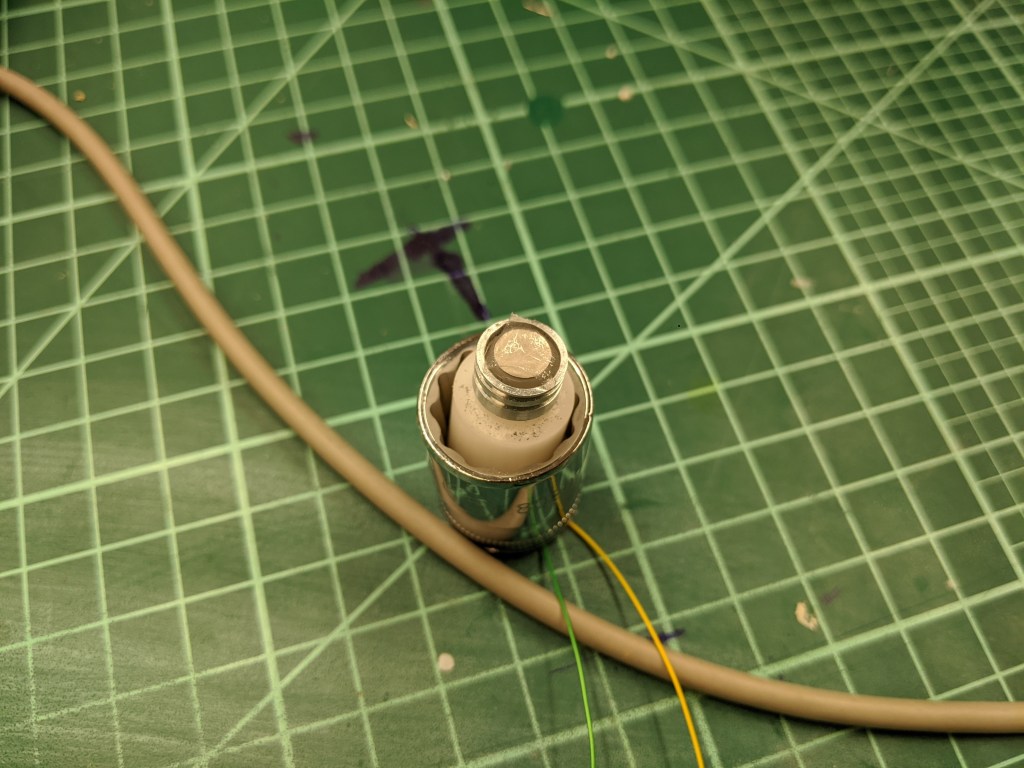

The best way to achieve this fixturing seems to be an aluminum block (safe to laser), then a layer of removable double sided tape, then another layer of painters tape, then the aluminum stock. Without the layer of painters tape, the aluminum card is hard to remove without bending. The painters tape releases from the doublestick pretty cleanly, so a single doublestick tape bed can last many laserings.

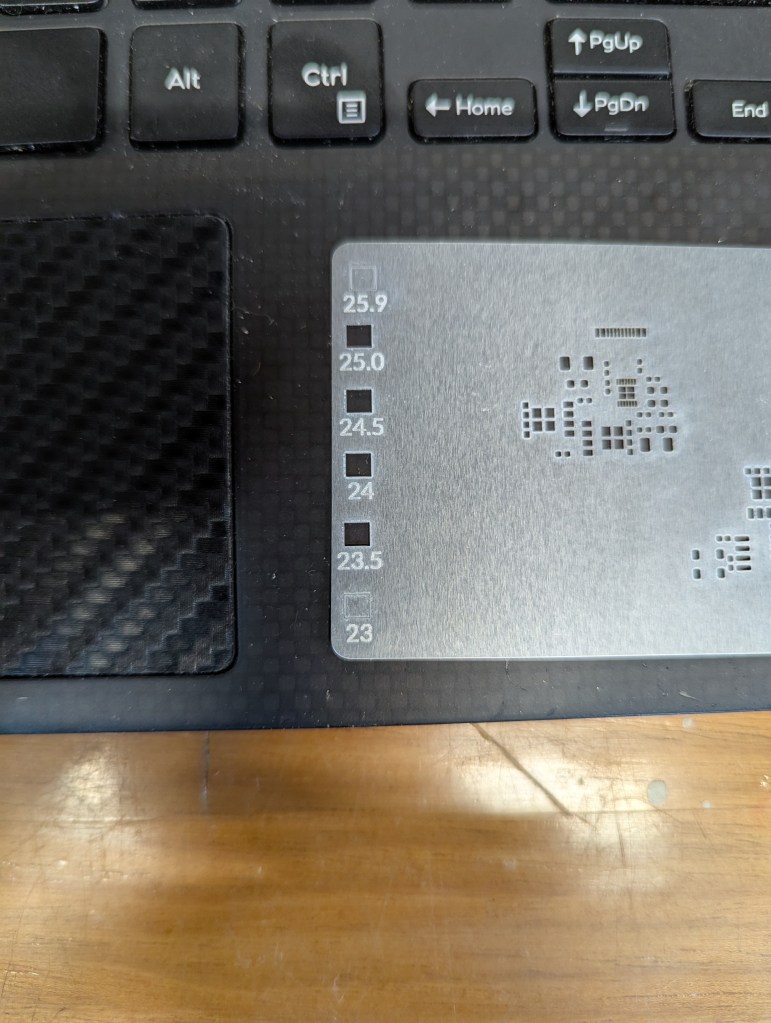

Focus Focus Focus

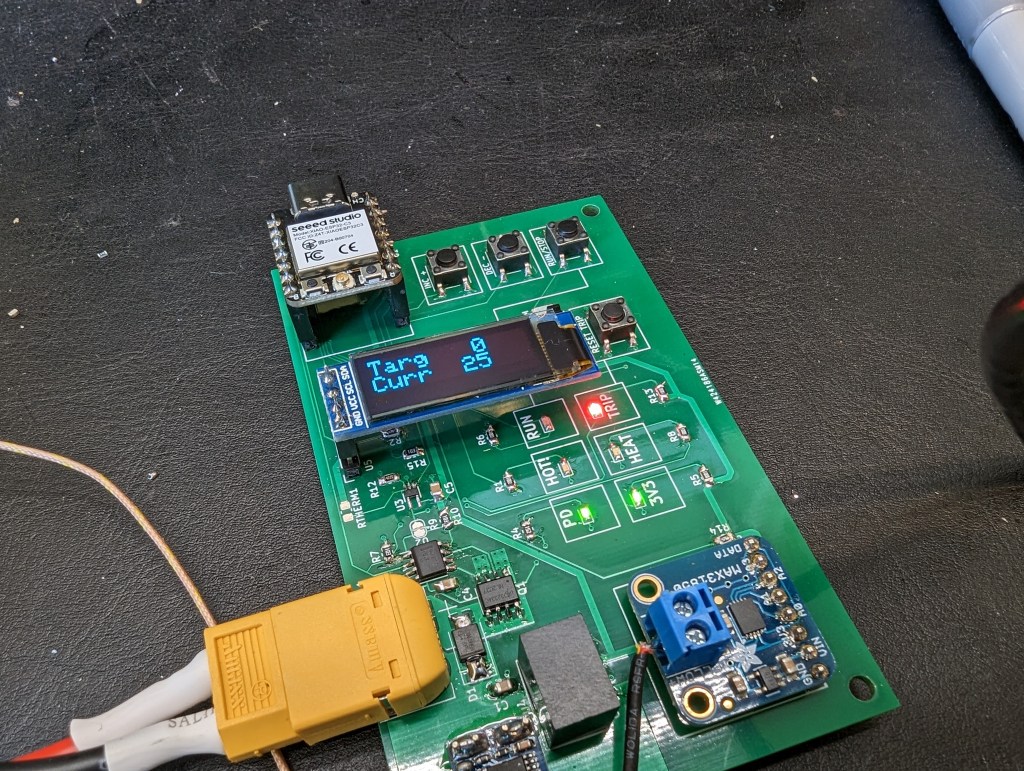

One issue I have run into repeatedly with this laser is that the autofocus does not work, at all. I guess its better than nothing, but I find that its off by about -3mm-4mm. So every time I create a new fixture, turn the machine on, or jog anything, it needs refocusing. I just start by taking the autofocus distance, subtracting 3, then I focus by .5mm increments until I go through a “sweet spot”. It seems like for metal ablation, the beam is tight enough to be focused over about 1.5mm

Surprisingly, the laser cutting makes a distinct snapping/humming sound when its cutting well. I assume this has to do with the metal rapidly expanding/contracting as the laser heats it up and deforms it.

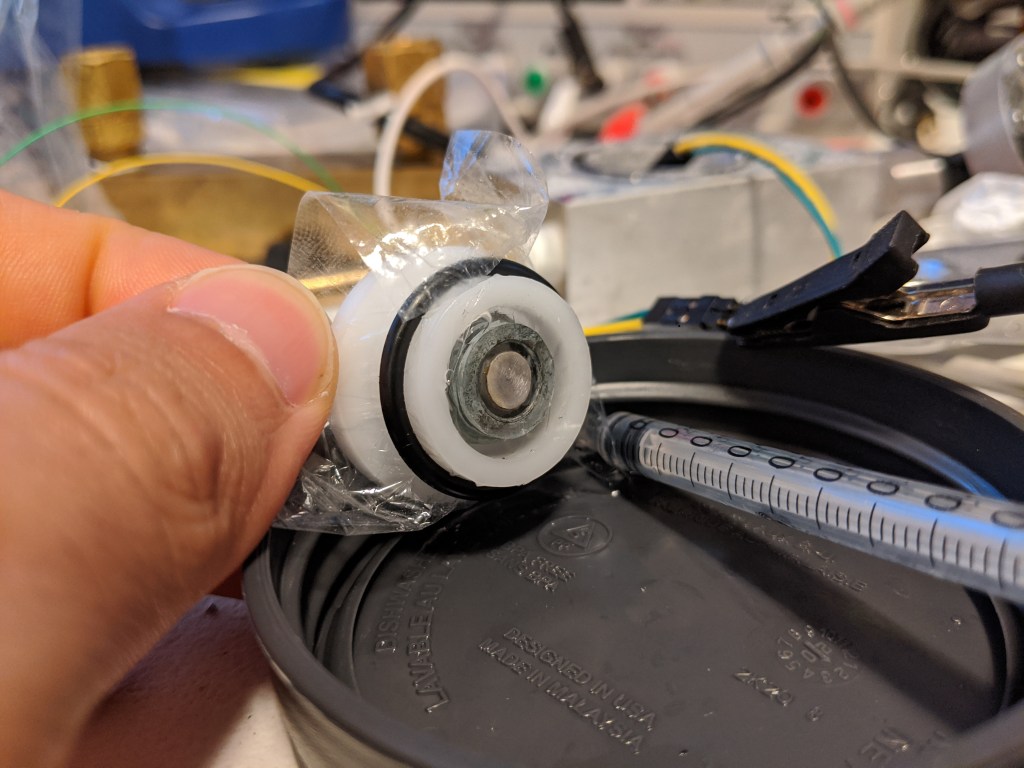

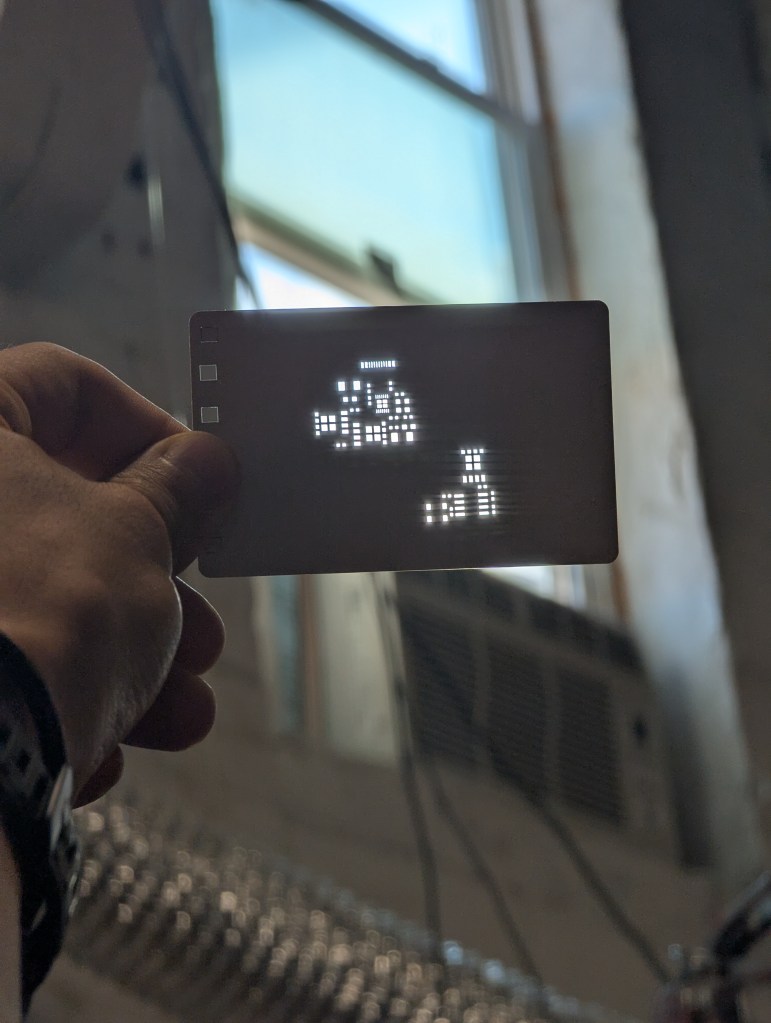

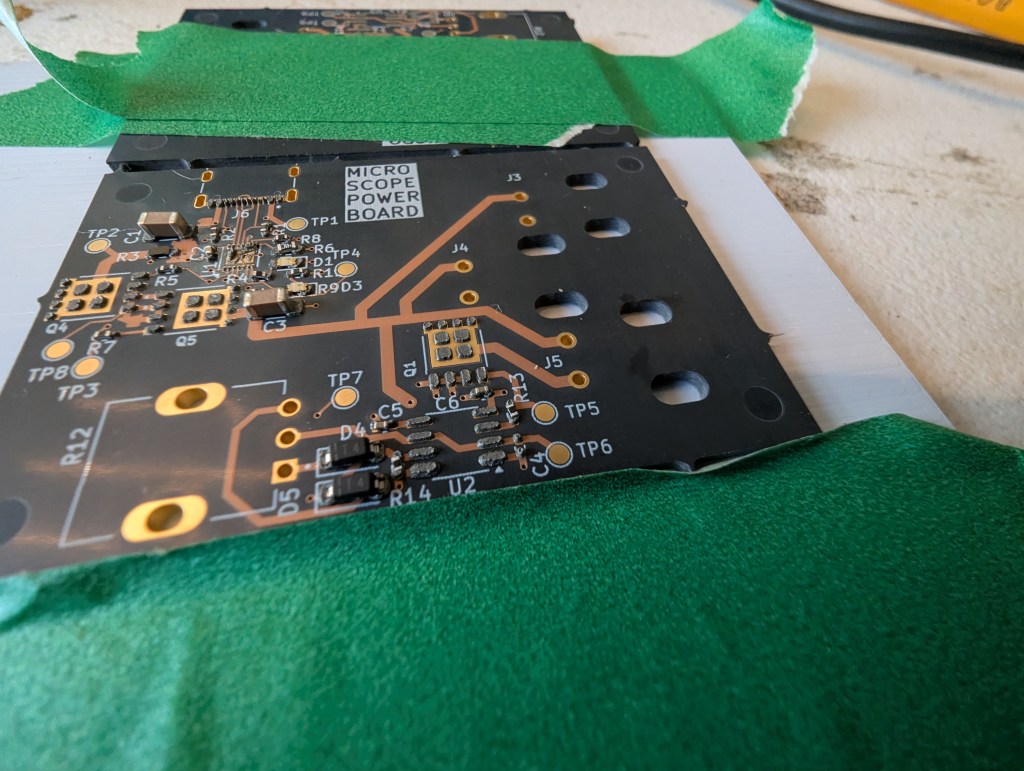

Stencil Performance

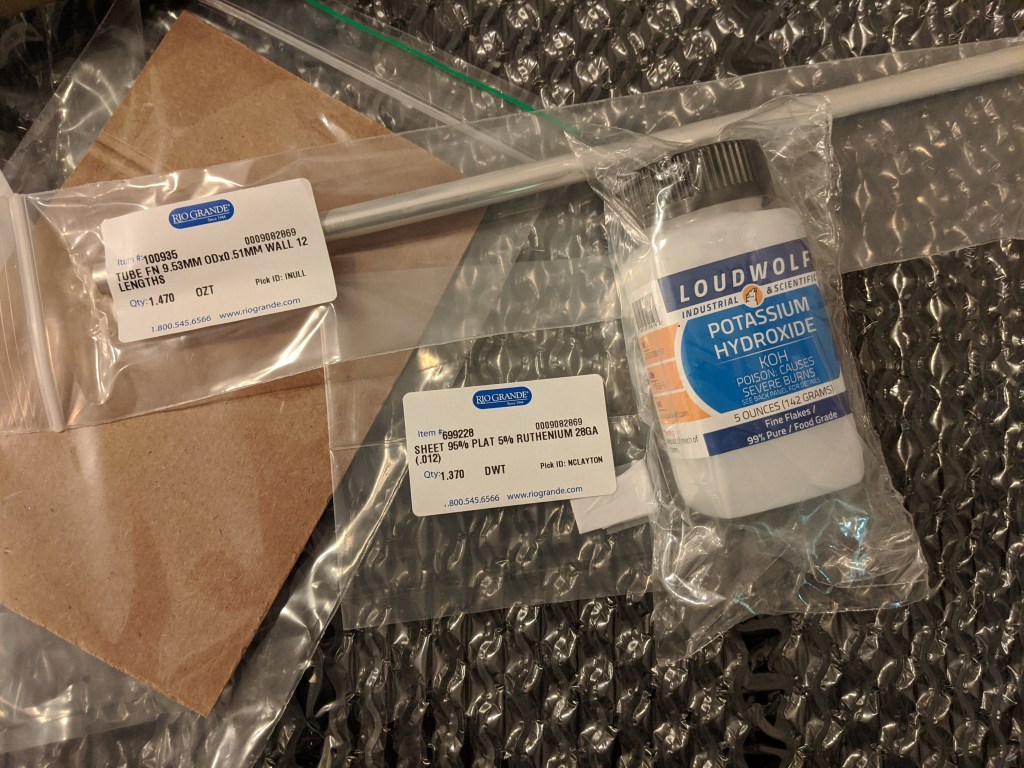

My hope is that this can make stencils for everyday use, and for emergency use, like pcb rework. PCB stencils usually cost a couple bucks and cause a few cost related problems for ordering PCBS – specifically in the US, the stencils are relatively expensive (if coming from somewhere like sunstone), or you have to get them at a separate website with separate shipping (osh park/osh stencils), or if you are ordering small boards from overseas, stencils make shipping really expensive as dimensional weight goes up (the box is bigger).

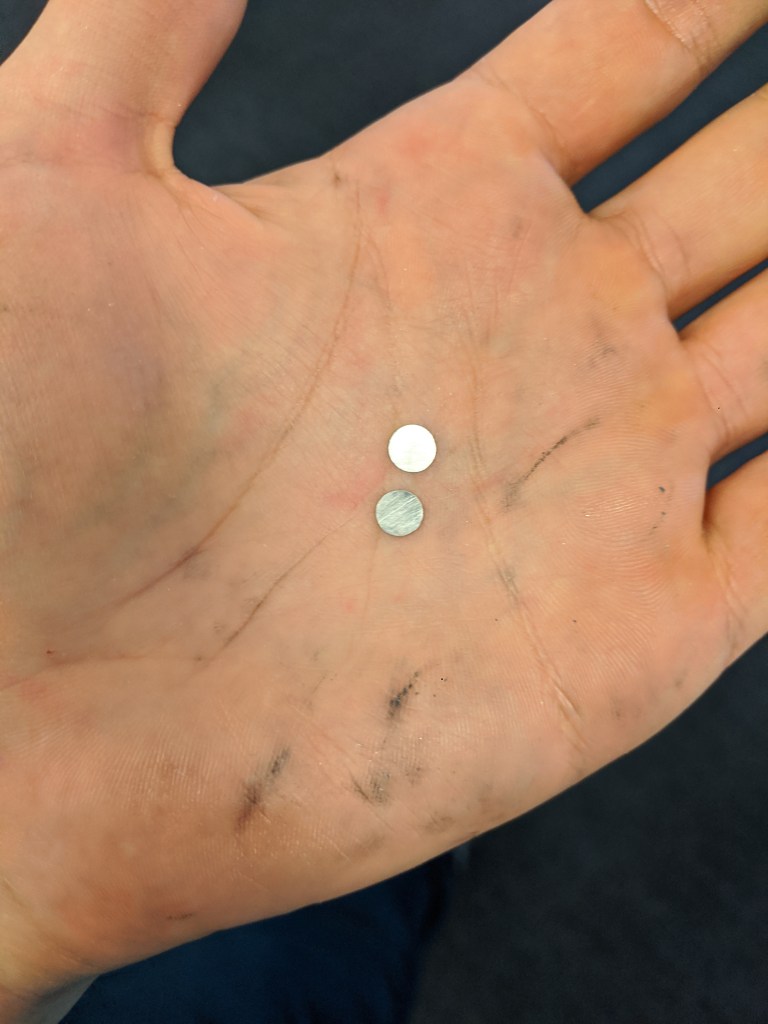

This stencil was quite usable, but it seemed thick (around .18). In the future, I’ll try a slightly thinner material to reduce paste application, especially for “middle”/large pads. The good thing is that its easy to delete or reshape the windows for components if they cause trouble!