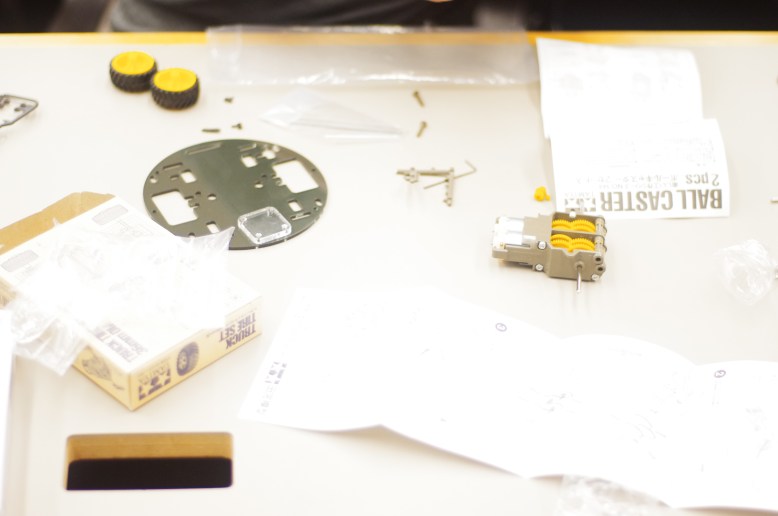

Today was “Day 0” of the GFP project. Today, I showed everyone how to pour plates while practicing (some amount of) aseptic technique. This is a walkthrough of preparing LB plates from mixing the agar, to how the plates should be labeled.

Things you will need:

- Dry LB agar mix, OR dry LB and dry agar

- a scale, accurate to tenths of grams

- weigh paper OR regular paper OR aluminum foil

- some kind of pressure sterilizer (like the ones used in canning, or an autoclave)

- sterile petri dishes- pre-sterilized disposable dishes, or glass dishes

- Distilled or Reverse Osmosis water, depending on how sensitive your organism is

- a bottle to hold your nutrient agar, with a lid.

1. Plan out what you are going to make

Read the instructions!

Plan out how many plates you are going to make. A regular sized dish will hold about 20ml of agar comfortably. Today we wanted to make 5 plates, so I knew we would need about 100 ml of media. I know that the pre-mixed LB agar uses 37 grams/liter, so for 100 ml (1/10th of a liter), I would need. 3.7g of dry media. I you have bought agar or media-agar, check the bottle for how much you should add per liter.

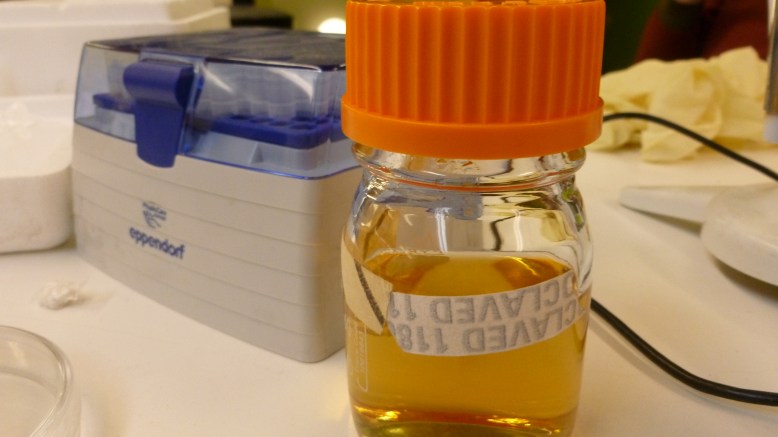

At BOSSLAB, we use a pre-mixed Miller LB+agar mixture. It is important to know that LB does not always come with agar, and agar does not always come with LB. LB stands for Luria, Luria-Bertani, or Lysogeny broth depending on who you talk to. LB is made of digested Casein, yeast extract, and sodium chloride. The digested Casein protein provides peptides (short amino acid chains), while the yeast extract provides vitamins and trace elements. The salt in the Miller formulation of LB is a bit higher, at 10g/L, which is normally to provide the right osmolarity, but in our case it is just because it is what we have. Agar is a sugar purified from seeweed, that when added to water and dissolved, cools to form a jello-like substance. When mixed, you get LB-agar, which forms solid plates.

2. Add Water

Adding RO water!

Now that you have everything planned out, add your DI or RO water to your bottle. Water comes before the dry stuff because the dry stuff tends to form clumps, and if this happens in the bottom of the bottle, or worse, a conical tube, it might not get mixed into the media. Right now all the media and water we are dealing with is “dirty”, so don’t worry about aseptic technique.

3. Measure the dry powders

measure the dry media

The next step is to measure out your powders. For this you will need the scale, and your weigh paper or foil, and your dry media. I like to use foil because we have it in the lab, but remember to flatten it out so that the powder doesn’t get stuck in crevices. If you are using paper or foil, fold it in half so that you can pour the powder out. Place the weigh boat/paper on the scale and tare, then measure out however much of the dry media you need.

4. Mix!

Now just drop the powder into the water! It might need some convincing to completely break up and dissolve, so don’t be afraid to vortex or give the bottle a shake.

5. Sterilize (both heat and filter methods covered here), also sterilize your plates if you are using glass

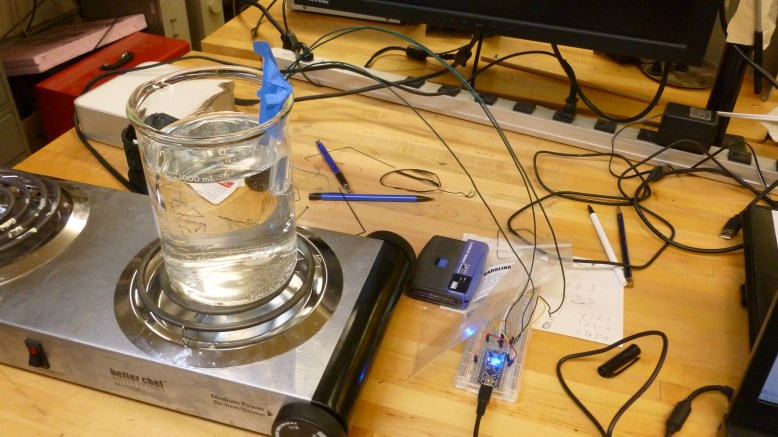

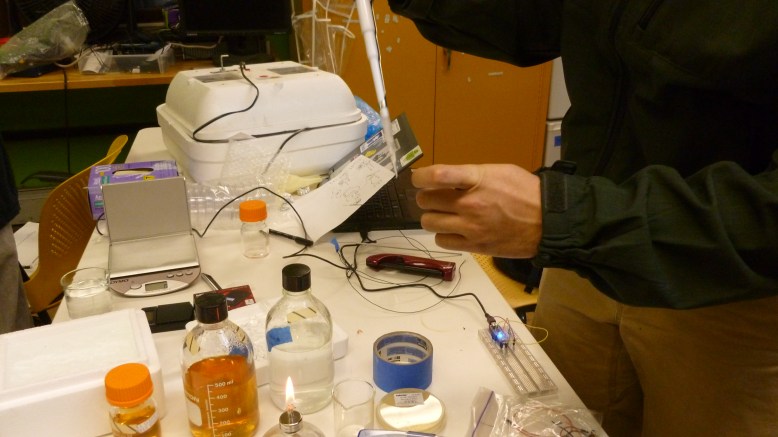

Time to fire up the cooker!

Before you set your sterilizer to “kill”, LOOSLEY screw the cap onto the bottle or cover it with foil. Securing the cap all the way can lead to exploding and other bad things, like the media not being subjected to the extreme pressure of the sterilizer. If you have access to a real autoclave, go ahead and put it in on whatever cycle the manufacturer recommends. If you are using a pressure cooker, you want to cook it at 15 psi for 15 minutes, unless you are trying to sterilize large volumes of rich media. For large volumes of rich media (more than 100-200 ml, I would say) you want to run it for as long as 30 minutes to make sure you kill EVERYTHING.

The other way you can sterilize media, which is more convenient, but more expensive per L, is filter sterilization. Some things, like antibiotics, must be sterilized this way because heating them destroys their antibiotic effect. Some things must be sterilized like this because they are volatile. However, some chemicals require special considerations; DMSO must be filter sterilized, but it will eat (dissolve) your filter if you do not choose one that is specially chemical resistant. Disposable filter sterilization units normally come with a hopper, or input, a filter with a vacuum inlet, and sometimes come with a pre-sterilized bottle for the final sterilized media. What you do is you apply a vaccuum to the bottom of the filter, pulling the media through into the clean bottle. This is suitable for some media, but not all, and you do need a vacuum pump or manifold.

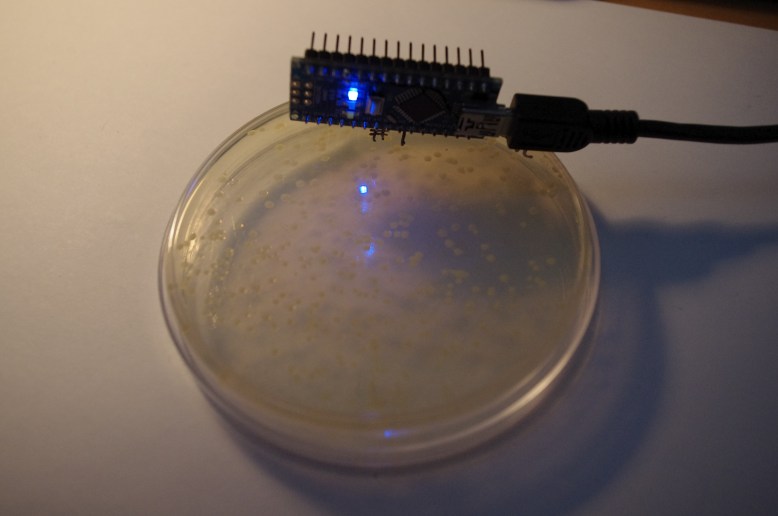

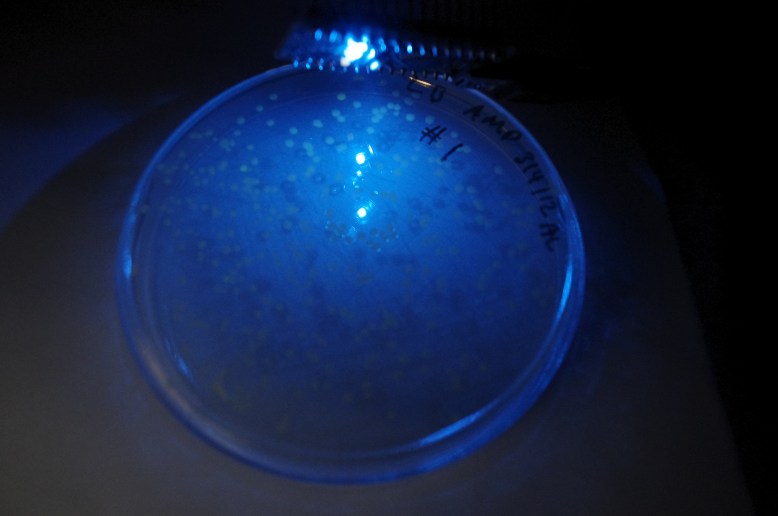

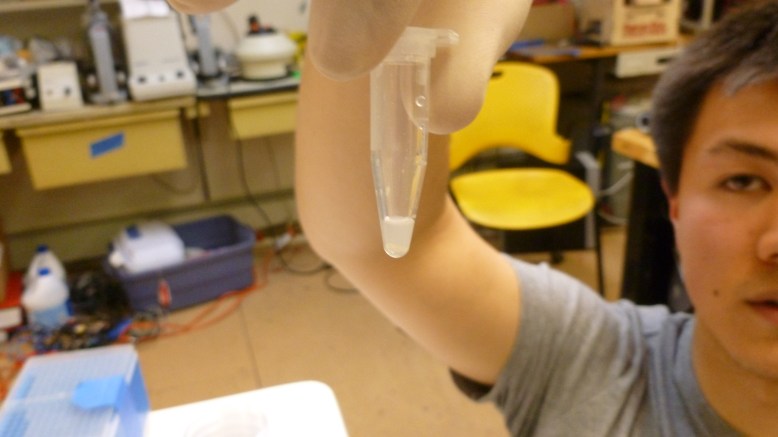

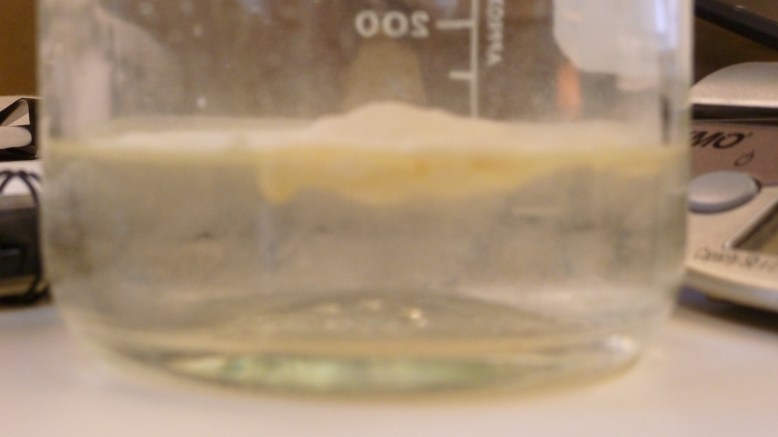

At this step, your media should be a liquid and somewhat hot. If it is not, it can be restored to the hot, liquid state by microwaving it inside the sterilized container.

6. prepare to pour plates

At this point, it will be hot and a liquid. Use autoclave gloves!

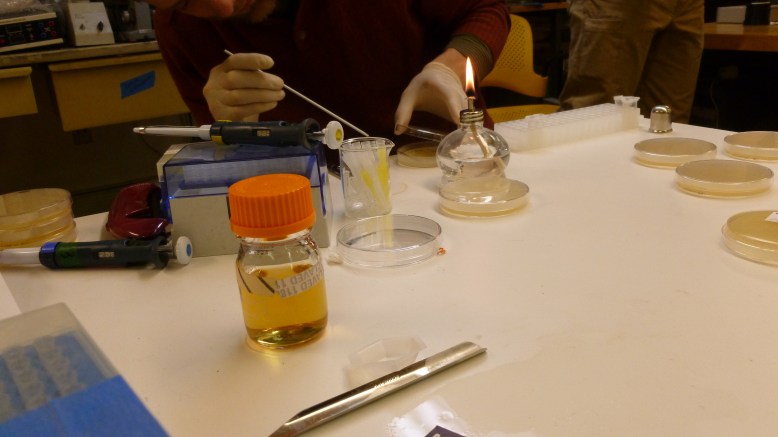

Get ready to pour your plates by wiping down your work surface with alcohol or bleach. This is extra-important if you are working somewhere dusty or with particularly hardy microbes, to kill things that might get stirred up by moving stuff around on the table. Remember, dust is BAD and falls DOWN, onto plates. To counteract this, you want to have some kind of open flame to create convection currents. A lighter is too little, and a campfire is too much. A Bunsen burner or alcohol lamp is just right. Get your plates ready by putting them right side up (big clamshell up) on the table. If you are only making one thing, or you know what plate will get what kind of media, you can write on the bottom of the plates now. You should write what kind of media it is, the date prepared, and your initials. If I were to make some plates I would write “LB 2/27/2012 A.L.” along the rim of the bottom of the bottom plate.

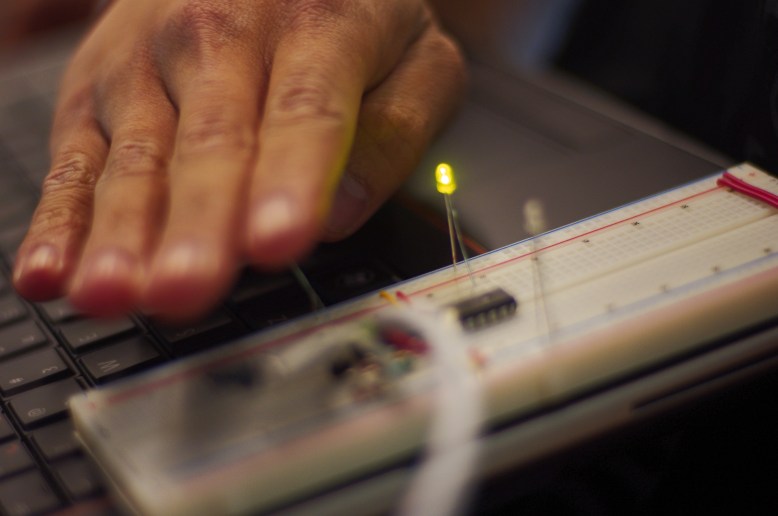

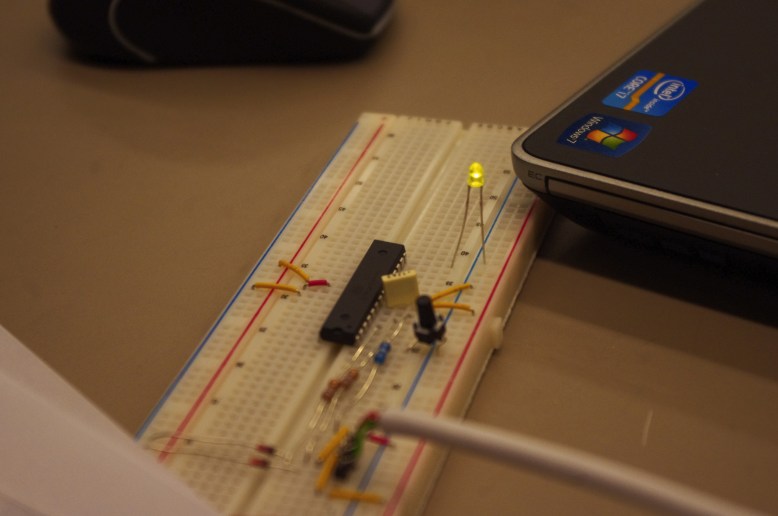

7. Pour the plates!

Ben carefully pours a plate

At this point, your media should be a hot liquid, and easy to pour. With your fire on, go ahead an open the bottle, placing the lid face down on the table. Quickly flame the mouth of the bottle to kill anything that may be hanging out there on the outside threads/inside mouth, and then pour the agar into the bottom of the dish. The agar should just cover the entire bottom of the dish, and should be a 3-4 mm thick. When you open the dish, you should place the cover FACE DOWN on the table, so dust does not get in it. After the plate is poured, cover it back up ASAP. Once you have poured all the plates, or if you take a break, or before you put away the media bottle, flame the mouth of the bottle again, just to keep it clean. Once everything is sealed up, you can turn off the flame. and let the plates set (like jello!).

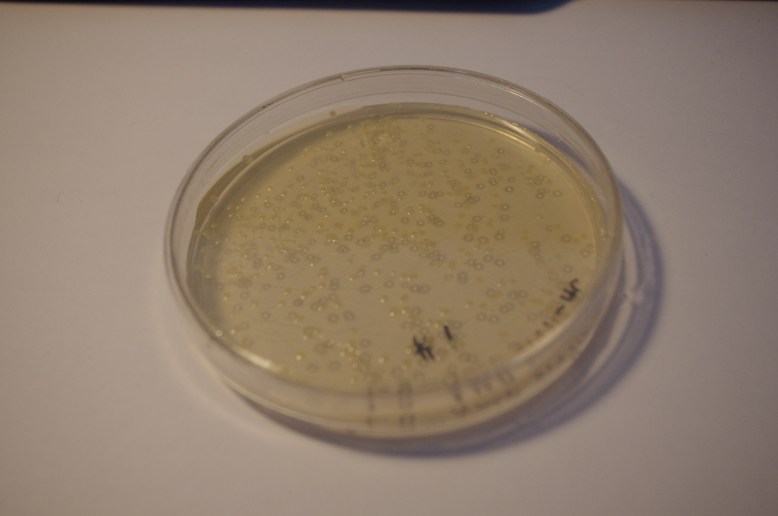

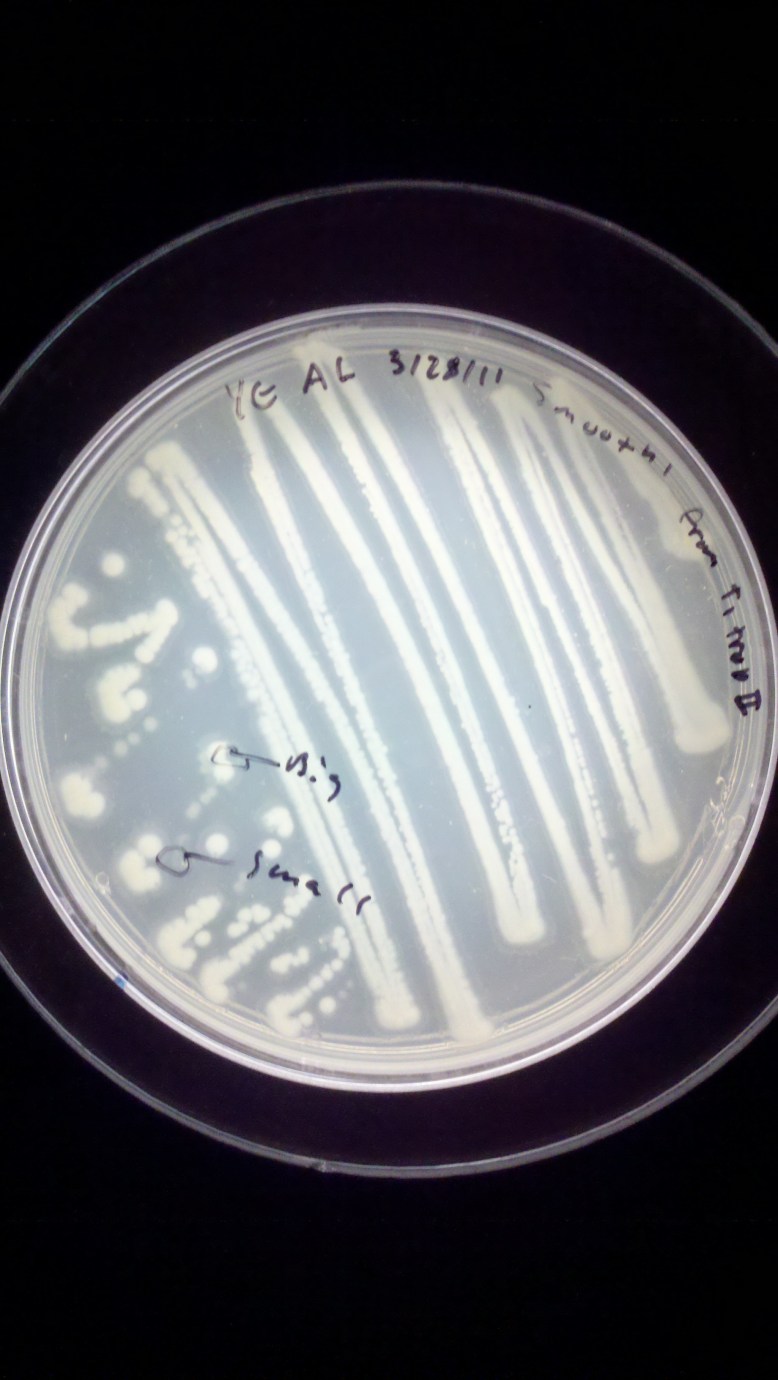

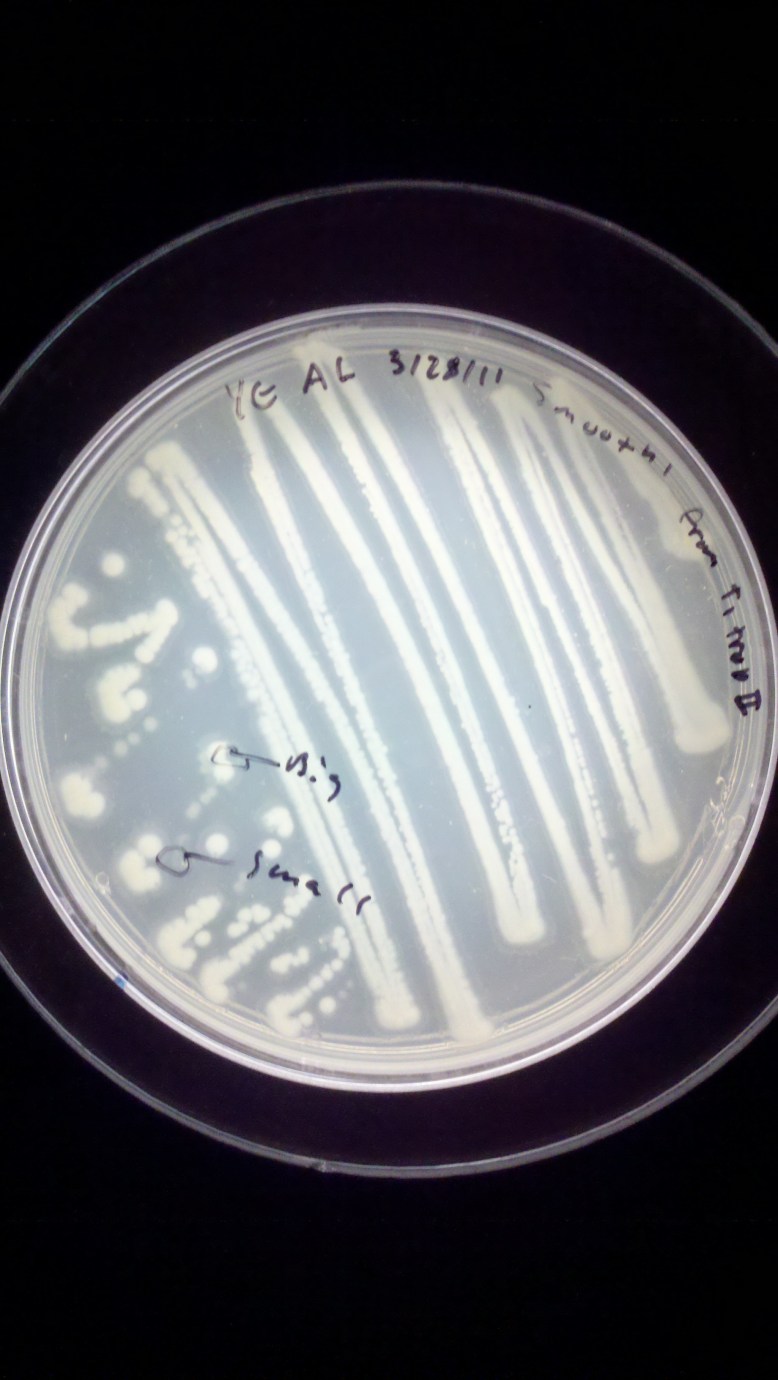

8. Once the plates are set, write what the plates are on the outside of the bottom plate!

As you can see, this is a Yeast Extract plate, streaked on 3/28/11 by me with Smooth’ from a plate called T1 trop II

This step is important for the safety of those around you, and your own sanity. ALWAYS write down the type of media, the date it was made, and your initials on a plate. This is so people can refer questions like “is this yours” and “is it dangerous” and “can it be thrown out” to you. It is also helpful for your records to know what you are growing these things on.

Well, thats it. Good luck to you, citizen scientists!