Gas, for the most part, should stay inside of a closed circuit rebreather- that’s sort of the entire point. So leak testing is very important- important enough to automate to get really good data. Unlike reading a gauge with your eyes, automated data capture, if done right, can make it easier to capture a lot of data, and it takes out errors caused by a person interpreting an analog gauge face. I also wanted to add temperature measurement, as that seemed likely to cause pressure deviation, even to the point that the pressure in the volume under test seemed to go up.

Test Setup

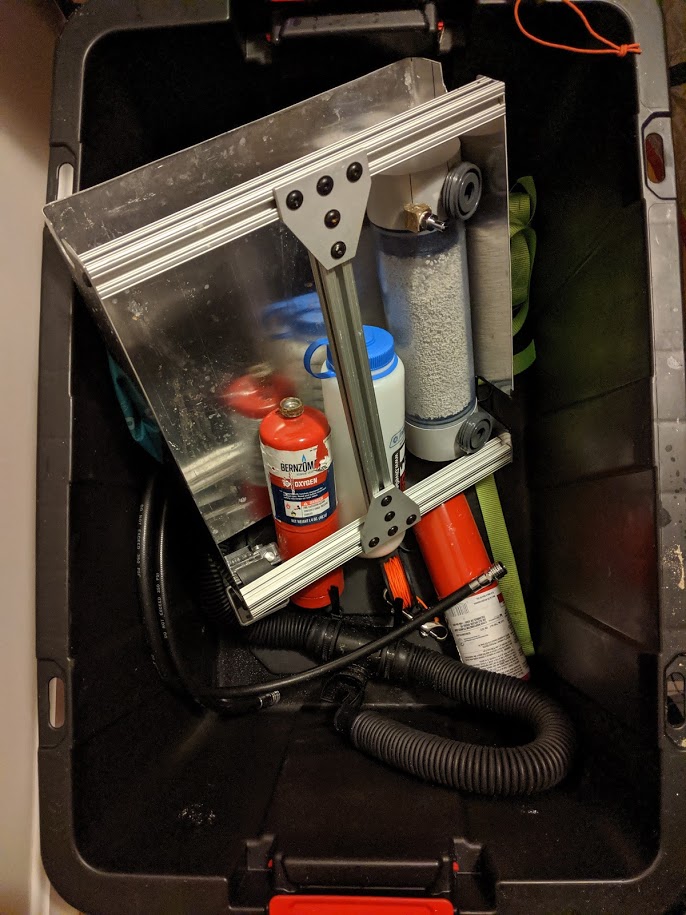

Automated data logging is nice since it is much less tedious and usually allows for a lot more data and more data sources to be reliably sampled. In this case, I didn’t have a lot of bench space to dedicate to this, and the sampling rate was low, and I wanted to use stuff I already owned. So I ended up using an arduino as the “data collector”, a MAX31850 as the temperature sensor, and a the dwyer 605-20 as the pressure sensor.

I think the most annoying part of this is the pressure sensor- its just not really meant for this application, as its powered at a somewhat high voltage (10-35 VDC) and outputs 4-20 mA (current, not voltage) across the span of 0-20″ of water. While measuring the current is possible, and even possible to automate with some of my gear, it would take up a good amount of space, and it not really necessary.

Of course, since the pressure sensor basically becomes a current source, it is possible to stick a resistor in there to create a voltage drop. The resistor can’t be too big (requiring too much current) and making it too small will mean there is not a large enough voltage drop. I managed to find a 200 ohm resistor in my junk pile, which turned out to work well:

Output Voltage:

.02 A * 200 ohms = 4 V

.004A * 200 ohms = .8 V

Max Power Dissipation:

200 ohms * (.02 A)^2 = .08 WAccording to the datasheet, 200 ohms and running at 15 V would work fine for the pressure sensor, so I had to pull out a power supply. It seems weird that I could turn the voltage up to 35V and still have the pressure sensor work fine and output the same voltage, but I guess that is the magic of it being a current source.

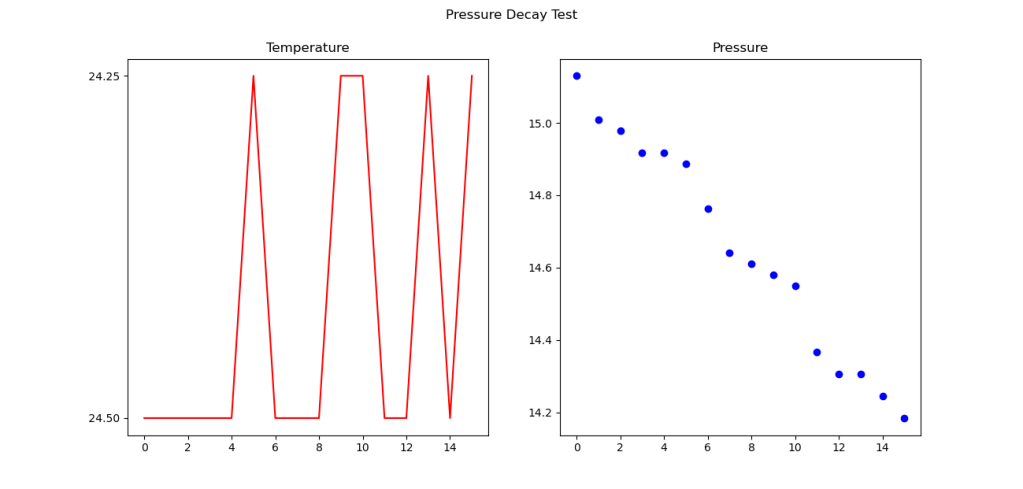

Sample Data

Here we have 15 minutes of data- it was being recorded every 1 minute. As you can see, the pressure dropped about 1 inch of water over that time period, with little change in temperature. Since I have a differential pressure gauge, changes in barometric pressure should be zeroed out. So we can finally observe a leak! Given a rough volume of 13 liters (stated volume of drybag), and a nominal room temperature, it comes out to about 30 ml of gas lost over 15 minutes.

How Good is Good Enough?

People say that if you can measure it, you can change it. That might be true, but making something completely leak proof is more or less impossible- just keep looking and you can find a leak at some pressure or with some penetrant (like helium, a very small gas!). It’s important to know when something is good enough!

EN-14143 is a European standard for rebreathers, so lets look there for some leak rate and pressure information.

5.6.5 Exhaust valve

from EN-14143 which I found somewhere online. Emphasis mine

The apparatus shall have an exhaust valve, operated automatically by excess gas in the breathing circuit.

The exhaust valve shall prevent the pressure in the breathing circuit exceeding 40 mbar.

Testing shall be done in accordance with 6.5.3.1 after the test according to 6.5.3.2.

The operation of the exhaust valve shall not be degraded or leaking after being subjected to

a) a constant flow of 300 l min-1 for a period of 1 min;

b) a static negative pressure of 80 mbar for a period of 10 s (when in the wetted condition).

The leakage of the exhaust valve (when in the wetted condition) shall not exceed 0,5 ml (STP) min-1 when

tested with a negative pressure of 7 mbar for at least one minute.

According to this, the maximum pressure the device should experience is 40mbar across the counterlung. Anything greater should be vented by the overpressure valve. Additionally, it looks like .5ml/min of leakage at 7mbar (2.8″ water) is permitted. At a higher pressure of 15″ water, it seems like the leak rate is about 2ml/min. This is encouraging since this is the leak rate for the whole system, at a much higher pressure. However, it still merits a test around 3″ of water.

Another analysis would be to consider gas supply vs leakage, since there is not a lot of gas in this rebreather. Assuming a worst case leak rate of 2ml/min, for a 30 minute dive an additional 60ml of oxygen would be lost. As a person requires somewhere around 500ml-1000ml of oxygen per minute, this seems like a very small amount to loose- less than a minute of dive time.

Overall I am surprised and pleased with the leak rate, and with an automated setup, it should be easy to take a look at this whenever I want, or across different devices and iterations. Fortunately, it looks like I might not need to do much to reduce leak rate.