The GFP project rolls forward! Powered (funded) by the people doing the work, I managed to order all the materials that we would need for a transformation this weekend (by that, I mean today). There was an awesome turnout; some new people came out, a lot of supporters came out, and a good time was had by all.

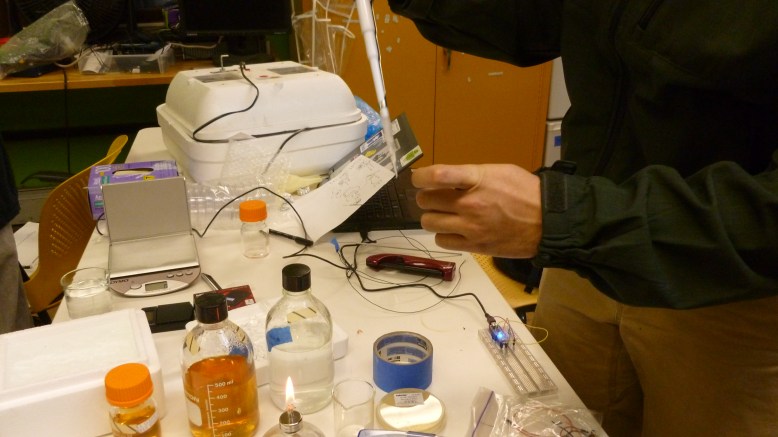

From left to right: LB broth, LB agar, 50 mM CaCl solution, alcohol burner, tape, streaked plate, arduino, pipettes in a fancy box, ziplock-o-wires

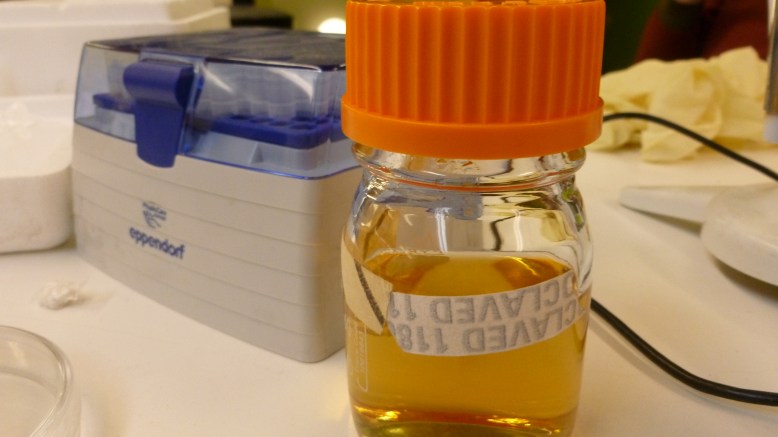

To start out, we had to sterilize some media and CaCl2 solution. We made 200 ml of LB agar, 80 ml of LB broth, and 500 ml of 50mM CaCl2 salt solution. The LB agar was used to make LB+ ampicillin plates. These were prepared by adding 2 ml of 1% ampicillin to the still-molten agar once it had cooled to “warm enough to hold”, and then pouring it into sterile petri dishes.

The Calcium Chloride solution and the LB broth were needed for the transformation. You only need 250 ul of each per-transformation. We prepared the LB broth in bulk because it is useful to have on hand, and we prepared way to much CaCl2 because our scale was not sensitive enough to measure out a smaller quantity that would make a 50mM solution. We could have made a 1M solution and diluted it, but it seemed simpler to just make 500ml.

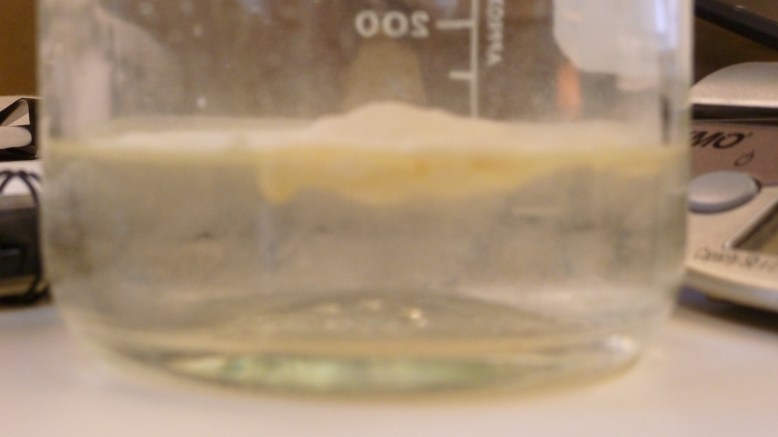

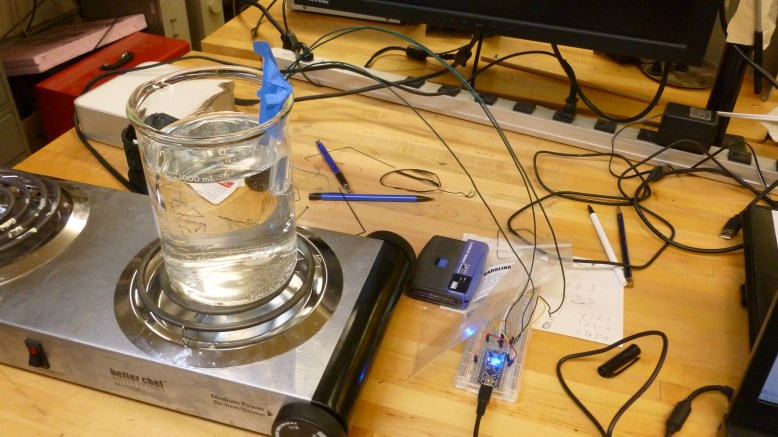

The other necessities for the transformation that had to be prepared were the ice bath, and the 42 C water bath. The ice bath was created using the insulated shipping crate that the plasmid and ampicillin came in by throwing some ice in the larger (bottom) container. The water bath I have successfully made before by nuking (microwaving) the water and then guesstimating that it was hot enough (more than body temperature, but cool enough to hold, between 37-50C). Today I used what seemed to be a much more reliable method, which was a hot plate and a submersible temperature probe.

(Hot) Water bath setup. Sensor in falcon tube taped to beaker, arduino connected to sensor and computer

The temperature probe was improvised with my arduino mini, a DS1820 digital temperature sensor, some long wires, and a 15 ml falcon tube. I submerged the falcon tube in the water bath, and stuck the temperature sensor (which had been soldered to the long wires) into the tube, allowing it to (hopefully) measure the temperature of the bath. This was reporting the temperature back to my computer with some script I got to work a while ago. A better way to set this up physiclly would be to cram the sensor in to a thin-wall reaction tube (PCR tube) and fill it with milliQ water (non conductive, very DI RO water), stick the sensor in the water and waterproof all that with sugru or epoxy. This way there would be no air gap, and the sensor would be safe in DI water.

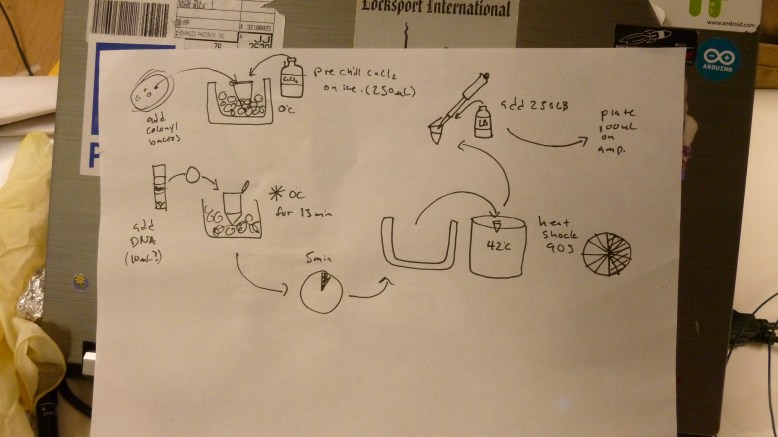

During all of that setup we were also preparing the bacteria for heat shock, teaching people how to pipette and streak bacteria, and talking about biology in general. Our transformation protocol, officially was this:

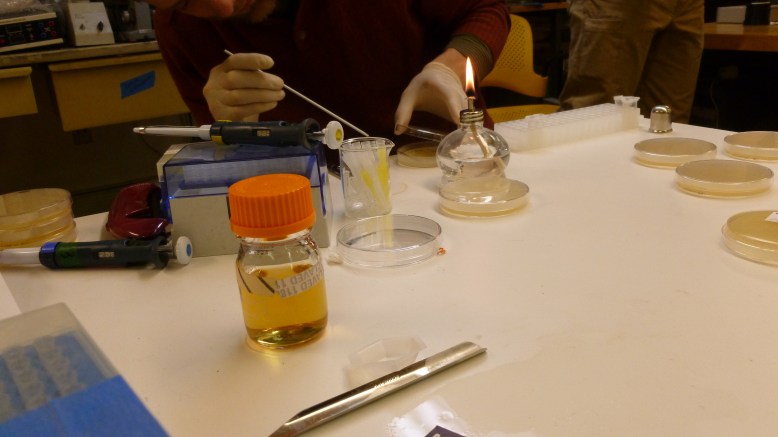

1. Gather reagents (LB broth, 50mM CaCl2, LB+Amp plates, e. coli plate, eppendorf tubes), prepare ice bath and water bath, and gather your tools (flame, inoculation loop, pipettes and tips)

2. add 250 ul of 50 mM CaCl2 to an eppendorf tube, and chill on ice

3. scrape off some e. coli (enough to see on the loop) with a flame sterilized loop, and swish the loop around in the iced CaCl2 in the eppendorf. Make sure they fall off into the CaCl2.

4. flick the tube until the bacteria are no longer clumped together. The solution should be cloudy now. Chill tube on ice for 1-5 min.

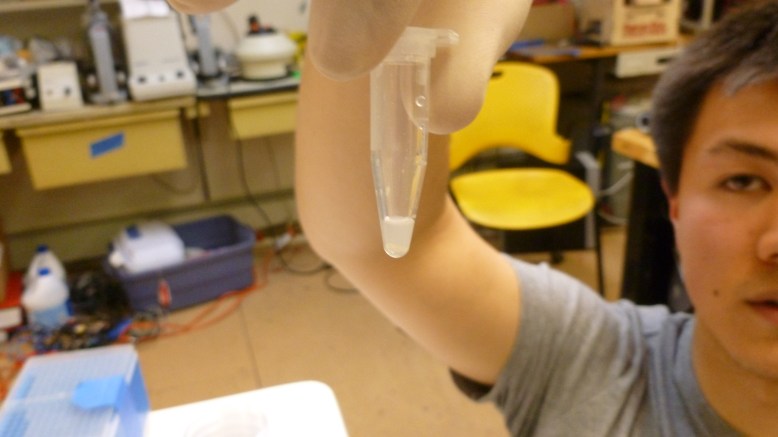

5. Add 20ul of plasmid DNA at .005ug/ul to the eppendorf. This is .1ug of DNA. Return tube to ice, incubate for 5 min

6. heat shock at 42C for 90 seconds

7. add 250ul of LB broth

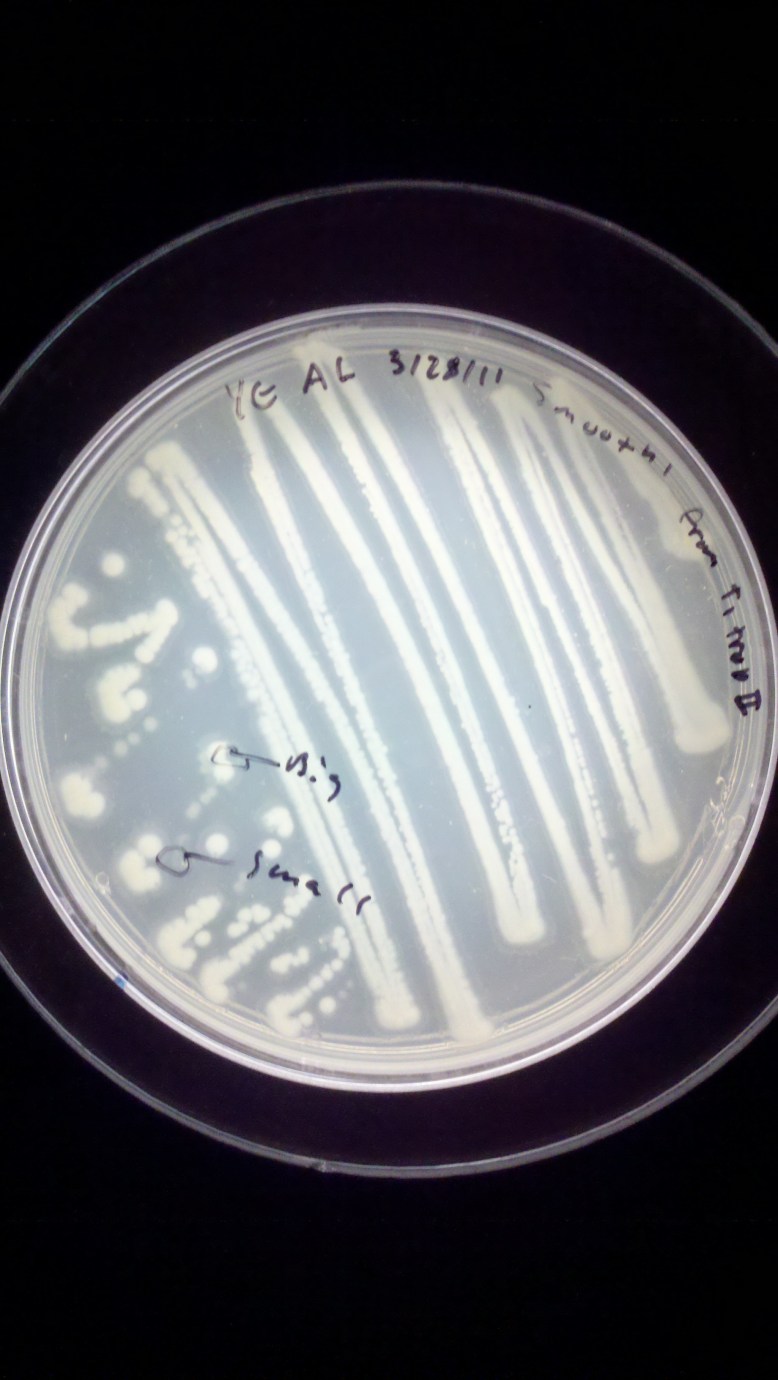

8. plate 100ul on LB+Amp plates. Pipette 100ul on to the plate, then flame loop and cool in agar somewhere that you did not pipette onto. Use loop to spread pipetted transformant mixture.

With all of that done, we cleaned up and headed off to wherever. Some people had to leave early, but most everyone seemed like they would be back! There should be results on if this worked in just a few days.