This summer, my housemate bought a fish. She named it “Maggie”, which is short for its real name, #MAGNUM. I decided that I too would like a fish that I could watch…in my room, on the couch, at work…Everywhere! Unfortunately, that kind of fish doesn’t really exist, so instead I made a website and hosted a webcam on it. I wanted to quickly document the process, as I found it somewhat difficult to find documentation on what I thought should be an easy process. Caveat: I have yet to do this in linux, as the software I used was windows-based.

There are a few things you will need before you begin:

1. wireless router login info.

2. Microsoft expression encoder 4

3. A legitimate copy of windows

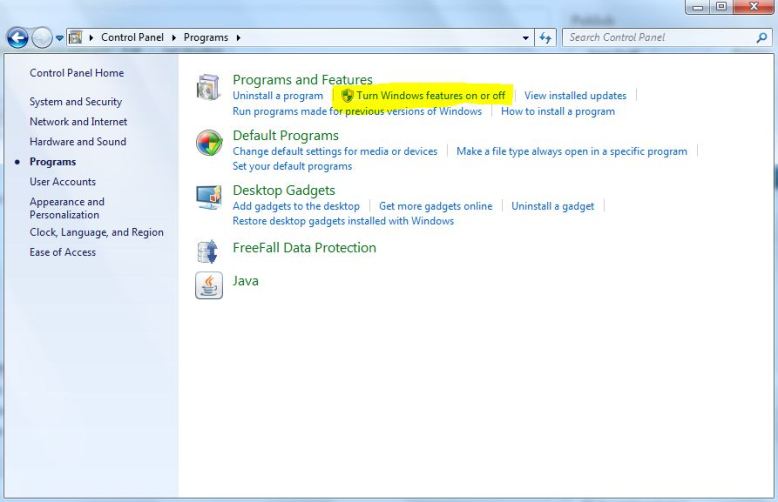

The first thing you should do is install Internet Information Services (IIS) on your computer. This is REALLY EASY, don’t be deterred by this step. Go to the start menu, open up the control panel, click programs, then got to the “turn windows features on or off” under programs and features. There should be a little shield next to it.

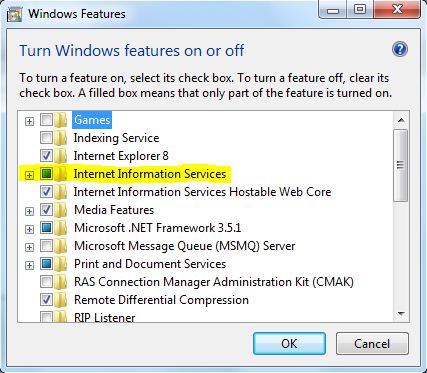

Since we are in windows, this will open yet another window with some kind of terrible check box/tree menu. You want to click the Internet Information Services button, then click OK.

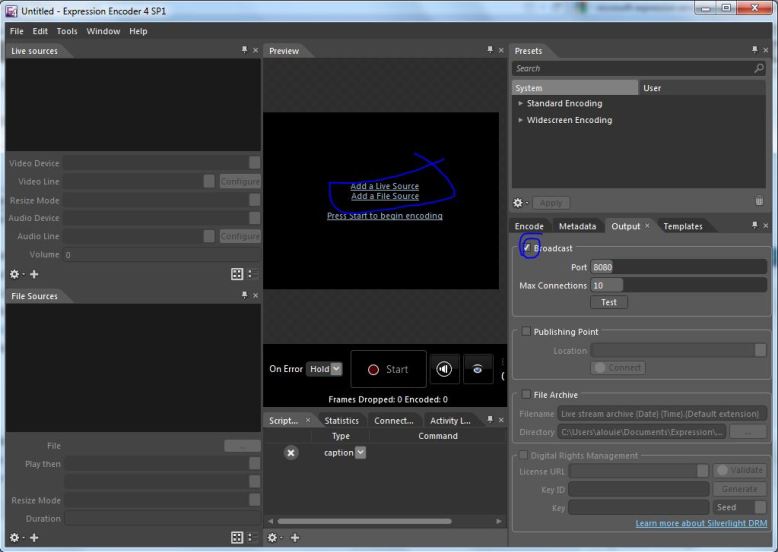

This should get IIS installed. In the mean time get a (legit, from MS) copy MS expression for free from here. MS Expression allows you to encode video as a wmv stream. Install it, open it, and click start broadcast project, and you should see something like this:

The first thing to do here is to click the check mark next to broadcast. You can leave those settings as they are, or play with them. By default, the broadcast should be on port 8080. Then click “add live source” right in the middle of the screen. The left pane should become active for clicking, and you can use the dropdown there to select your webcam. Once you do that, click start. You should see whatever the webcam is pointed at in the middle pane. Once that is done, it is time to set up your IIS server to host your website. Go to start, then open IIS. You should see something like this:

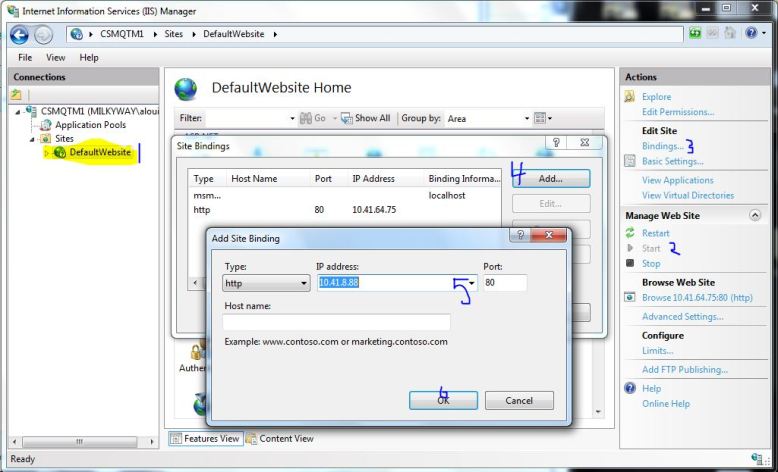

Now, the first thing you want to do is use the leftmost drop down pane to to navigate to DefaultWebsite. Then press start (right pane), if it is not already started. Then mouse up a bit and click on bindings. Click Add in the dialog that pops up. Yet another dialog will pop up. Use the dropdown menu for IP address and choose whatever IP happens to be there. Then click OK.

Now try clicking the button beneath “browse website” on the right pane. It should be some kind of IP address looking thing. The default iis startup webpage should appear. If that works, open up a new text document in [insert your favorite text editor here] or notepad. Paste this into it:

<html>

<!— BEGIN PLAYER —>

<!– webbot bot=”HTMLMarkup” startspan —->

<!– webbot bot=”HTMLMarkup” endspan —->

<!— end PLAYER —>

</html>

Replace the bolded sections with your IP (the one in IIS). It should read http://your.ip.here:8080. With that done, save it as an fish.html file and drag it into C:\inetpub\wwwroot. Now go to your http://yourwebsiteip/fish.html and you should see your live cam! Just like this:

Now there are two (possibly three) things you need to do:

- set up a static IP with your wireless router, and bind the website to that IP

- set up port forwarding on your wireless router

- use a service like noip to make sure your DNS doesn’t get dynamically reassigned.

These all assure that other people can access your website. 1 and 2 make it so people can connect to your website from your external ip (don’t know it? google “what is my ip”). Right now you are using an internal ip, and asking your router to connect to youself. If you try to visit your page from your external ip, your router will look for the webpage on itself, and then promptly return an error. Thats why you need port forwarding; it tells the router that when asked for a website (port 80) they should send it to your computer. The static IP will make it so that your computer is not re-assigned a new IP when you reconnect to your wireless network. Otherwise, it will get a new ip and the port forwarding will not work. The last thing (3) is only necessary if you want a really stable website, as your phone/internet company will occasionally change some DNS address and, again queries for your website will return errors. Services like noip will help you manage this.

I would write a guide for this, but www.portforward.com has excellent tutorials on pretty much every router, and much better explanations for everything. This is where I learned to do it, and I highly recommend using the website to do it yourself (however, I wouldn’t buy their product).

As usual, if there are questions/comments, ask away.