This is a reflection and analysis of how the first Secret Knowledge went. If you want the (polished) version of our actual activity, go here (link not active yet).

A few weeks ago, an email went out to the entire freshmen class of Olin College, aka “Students-Class of 2015”. The email was an invitation to learn “all the Secret Knowledge that they required”, if they would only come to the fourth floor (our secret lair) at 7:00 PM on a Friday. I expected maybe 10 people to show up. Neal and Kevin were less optimistic. In the end, we decided to print five copies of the handout we had prepared, and gathered up enough parts for five people. When 30 or so people showed up, we were both shocked and unprepared. Who knew that people wanted secret knowledge?

The first Secret Knowledge activity was based around a 555 timer. The goals of the activity were:

- Do something cool, and novel

- Learn to do something

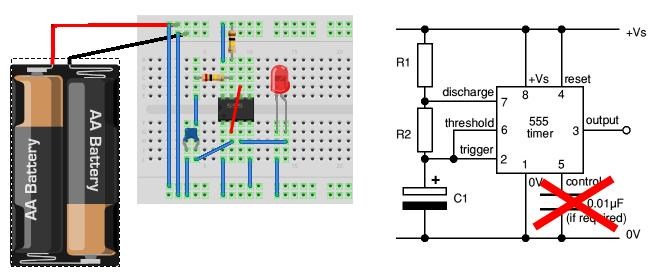

We achieved both goals, but not entirely successfully. The cool thing that we did was blink an LED. We did this by setting the 555 timer up as an astable multivibrator, or in layman’s terms an oscillator. The 555 directly powered an LED. The frequency of the blinking was variable when one of the resistors was exchanged for a potentiometer.

The goal that was not achieved 100% was the “learn to do something” goal. First I will explain what happened, and then explain what went wrong.

Even though we had plenty of components for everyone, we did not have a 1:1 ratio of person to breadboard. However, the real bottleneck to having each person actively prototyping and debugging their circuit was power. We didn’t have enough time to get 30 of one type of power supply, let alone 30 of any power supply, so we had about 6 power supplies of different types scattered around the room, ranging from computer ATX power supplies, to modified wall worts, to powered breadboards. We also made some slight errors in our handout for the activity.

We did account for people not knowing how to use a breadboard, which is why we included the diagram. However, the combination of the two diagrams were nearly useless because the students didn’t know the convention for numbering pins on an IC, and so they couldn’t correlate the numbering on the European-style schematic with the breadboard sketch (made in Fritzing). A similar problem was that we did not supply a guide as to what component was what in the diagram. Since we had expected a much lower turnout, we had expected to walk everyone through the process, step by step, troubleshooting on the fly.

The combination of these three mistakes made the situation chaotic, noisy and somewhat stressful. People were discouraged, I thought that we had given them the wrong components…and then someone got it. Slowly we realized the errors we had made and we corrected for them, by yelling things like “THERE NEEDS TO BE A WIRE BETWEEN TWO AND SIX!” and running around adding wires. I have to give props to Sasha (a random upperclassman passerby) here, because she decided to stay and help debug, which was super helpful.

We included a feedback section on the handout where people could write in what went well, what went poorly, and what they would like to build. This was unfortunately attached to the handout that we wanted them to keep, which is something we eventually changed (in later Secret Knowledges). What we learned from this was that people were curious about what was in the “black box” of the 555 timer, and that they were still mighty confused in about a few things that we had tried to teach them. The two prevailing positive comments were that building the circuit had taught them the most, or working with a partner had taught them the most. As far as things they wanted to build, most people wanted to make robots, or something that interacted with the world.

Based on the feedback we received, and what happened, I came to several conclusions about what we needed to do better. The first thing is that we needed to have equipment. Six power supplies is not enough for thirty people. The next problem was that we didn’t have a strong structure, which seemed to confuse some people, and caused them to drift off onto tangents when they went to build. We only talked for 15 or so minutes, and spent the rest of two hours debugging/building. Thats good talking to building time, but its bad that it took that long to build due to bad instructions.

Overall I would say it was a success, but that the program was definitely improved upon in later iterations. Things we took to heart were preparing handouts, and checking them for errors, as well as providing background. The next couple posts will be about parts II-V, and if you read them you can see how some of the things we did worked out (or didn’t).